Diplomacy in Action: Expanding the UN Security Council’s Role in Crisis and Conflict Prevention

1. INTRODUCTION: THE SECURITY COUNCIL’S LIMITATIONS

In August 2011, the UN Security Council initiated an ostensibly useful channel of communication with Syrian president Bashar al-Assad over the growing conflict in his country. At the start of the month, the Council issued a presidential statement calling for an immediate end to violence and “an inclusive and Syrian-led political process.” This was devised by three temporary members of the Council: India, Brazil and South Africa (IBSA). In mid-August, senior officials from New Delhi, Brasilia and Pretoria visited Damascus to follow up on the statement with Assad. The President promised them that he was committed to democracy and constitutional reforms, and added that his security forces had made “mistakes” in forcefully responding to peaceful demonstrations. There briefly appeared to be an opening for political progress, but the IBSA initiative did not go any further.

Opinions differ on why IBSA could not deliver more. Hardeep Singh Puri, then India’s permanent representative to the United Nations and an architect of the initiative, argued that while “there were reports – many credible – that Assad considered the idea of domestic reform and accommodation of the opposition” following IBSA’s intervention, the opposition “were not willing to meet Assad halfway.” Other analysts believe that the Syrian president was already set on a path of polarization and violence, and was not truly willing to take a more moderate course. Whichever view is correct,one point is clear: while the Security Council created space for preventive diplomacy in Damascus, it did not put in place any diplomatic follow-up mechanism to build on the IBSA visit, or to evaluate and aid any attempts by Assad to fulfill his promises of reform.

Although this episode ultimately proved to be no more than a footnote in diplomacy over Syria—and was soon overshadowed by much more confrontational diplomacy in the Security Council—it raises important questions about how the Security Council can engage more effectively in averting escalating crises and mediating solutions. It is a commonplace in diplomatic discussions at the UN that the organization as a whole, and the Council in particular, should focus more on preventing wars rather than just reacting to them. In September 2011, as the Syrian situation continued to deteriorate, the Security Council released a general statement “expressing its determination to enhance the effectiveness of the United Nations in preventing the eruption of armed conflicts, their escalation or spread where they occur, and their resurgence once they end.” Nonetheless,the 2015 High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) complained, “despite its authority under Article 34 of the UN Charter to become involved in an early stage in a dispute, the Security Council has infrequently engaged in emerging conflicts.

Like most other recent analyses of the UN’s preventive work, the HIPPO emphasized the roles of the UN secretariat, envoys and other tools (such as Special Political Missions) in prevention. But it also emphasized the need for the Council’s members to engage in direct crisis prevention and management work, in collaboration with the Secretary-General and secretariat, noting that “earlier Security Council engagement including interactive dialogues in informal formats and visits to turbulent areas would be important in addressing emerging threats".

UN crisis diplomacy does not automatically equate with actions by the Secretary-General, Secretariat or other parts of the UN family. Instead, there are many times and cases in which the most impactful form of UN action will involve collective or individual inter-governmental actions by Security Council members, often in partnership with other member states. There is a long but uneven history of Council members engaging directly in crisis diplomacy, in cases ranging from the Balkans in the 1940s to East Timor in 1999. Continuing this tradition, the Council has engaged in direct diplomacy in Burundi, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) among other cases over the last two years.

This level of diplomatic activism belies the widespread impression that the Council is doomed to paralysis. However, its efforts in these cases have also highlighted recurrent obstacles to Council action, including difficulties in defining common strategies and communicating consistent messages.

The Council’s role is also hampered by internal differences in how to process information on looming threats, procedural obstacles to rapid action, and a lack of strong institutional mechanisms for following up on initial preventive actions. If the Council is to fulfill the HIPPO’s recommendations on early action, therefore,it needs to review its working methods and operating procedures for direct preventive actions.

If the Council does not become more effective in this field, it is likely to cede political space to other coalitions of states and multilateral mechanisms in future crises. As the International Crisis Group (ICG) has noted, there is “a broader diffusion of conflict prevention and peacemaking responsibilities, with new powers, ambitious regional organizations and non-governmental actors taking roles that might once have been filled by the U.S., its allies or the UN.” ICG notes that one characteristic of this diffusion of responsibilities is a growing contest over “framework diplomacy” around crises, defined as “working out which international actors should (i) set strategies; (ii) handle direct contacts with key political actors; and (iii) manage information exchange and other practicalities [in a peace process.]”

Regional bodies and ad hoc coalitions have often proved better placed to undertake this framework-making role in recent crises. Examples of this include East African leaders’ decision to mediate the South Sudan conflict, sidelining a large UN mission, and Algeria’s leadership of talks on Mali. ICG has separately noted that “the UN leads no major peace process in sub-Saharan Africa” despite deploying tens of thousands of peacekeepers there.

This is not necessarily a bad thing: In many cases the Council is not the best mechanism for preventive diplomacy or conflict resolution. Indeed, it is arguable that the Council is innately poorly-designed to engage in certain forms of preventive action, especially when it comes to the early, quiet diplomacy required to nip potential conflicts in the bud. The Council also falls short in structural efforts to address the economic and social sources of conflicts. Even low-key Council interventions create intense political sensitivities, and differences among Western and non-Western members over sovereignty issues are a recurrent obstacle to early action. In many situations, other elements of the UN system—such as development agencies or the human rights—are much better positioned to take steps to prevent future conflicts than the Council.

Nonetheless, when and where crises escalate and conflicts are either imminent or underway, the Council is uniquely placed to mount an effective political response—at least in those cases where its members can agree on a basic framework for action. In theory, the five permanent members of the Council and their elected partners should have both the cumulative weight and diplomatic networks to persuade or pressure the parties to conflicts to back down. In many cases, such as Syria, power politics means this is impossible. But it is also notable that, even where there is some agreement in the Council over the need to avert or halt a conflict, its members can become bogged down in diplomatic scuffles over statements and resolutions. This means they spend remarkably little time directly engaging with the main players in the crisis, or trying to identify tailored diplomatic strategies that could offer a way out of violence on the ground.

The Security Council should shift its focus to greater direct engagement in conflicts, involving more strategic use of field visits along with additional mechanisms such as establishing Commissions including Council diplomats (and counterparts from other relevant states) to engage with crises at close quarters.

By becoming more operational, the Council may be able to reassert itself as a primary force in shaping framework diplomacy in many cases, rather than a relatively remote actor trying to shape UN crisis response through the niceties of resolution writing. This paper addresses these issues by (i) briefly highlighting the Security Council’s historical record in prevention and crisis diplomacy; (ii) assessing its current ability to engage directly in this field; and (iii) outlining a series of recommendations for strengthening its information-gathering, early engagement in crises and attempts to sustain peace.

While the Council is the master of its own procedures, the paper argues that the incoming UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, may be able to inform and guide the Council’s thinking. He has already urged the Council to make greater use of its non-coercive tools for the “pacific settlement of disputes” under Chapter VI of the UN Charter, and pledged to “support you [Council members] through the use of my good offices and my personal engagement.” Mr. Guterres has launched a new initiative to map the UN’s wider preventive capacities, and emphasized the need to link conflict prevention to the organization’s development activities. But there will be cases in which the Secretary-General and Security Council will need to join forces to manage the diplomacy around fast-moving crises together: this paper looks at how the Council could play its part in such diplomacy more effectively than has been the case in recent years.

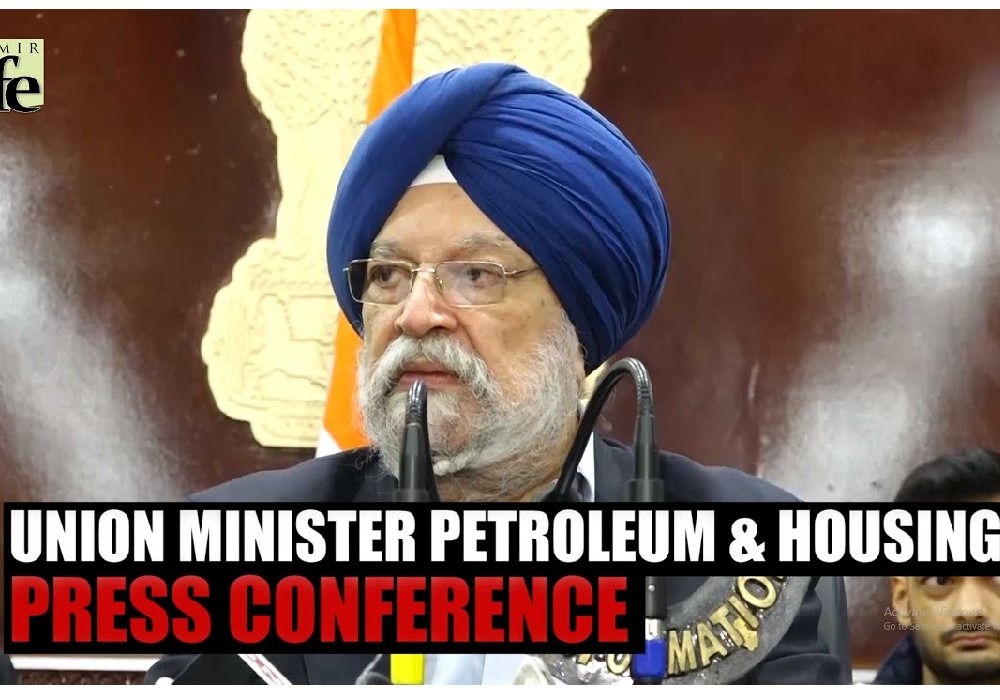

Synopsis Union Minister Hardeep Singh Puri stated India's commitment to an inclusive global energy future through open collaboration, highlighting the India-Middle ..

देश में एक करोड़ यात्री प्रतिदिन कर रहे हैं मेट्रो की सवारी: पुरी ..

Union Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas and Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri addressing a press conference in ..

Joint Press Conference by Shri Hardeep Singh Puri & Dr Sudhanshu Trivedi at BJP HQ| LIVE | ISM MEDIA ..

(3).jpg)

"I wish a speedy recovery to former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh Ji. God grant him good health," Puri wrote. ..