India’s response to state fragility in Africa

New Delhi is increasingly positioning itself as a significant player in African peace, security and development. Examining the question of how India responds to state fragility in Africa, this brief finds that India’s engagement is mostly transactional: working around, rather than on, sources of political fragility. Development and security interventions tend to operate in silos, but might change if Indian commercial investments are threatened by persistent instability. New Delhi’s pronouncements at global forums increasingly call for a more cohesive and comprehensive approach to development and security in Africa, while framing its own contribution in terms of building new development partnerships for mutual economic growth.

Introduction

Fourteen of the top 20 states listed in the 2017 Fragile State Index are in Africa.[i] Of these 14, India has ongoing investments in eight.[ii] Overall, India’s investments in the African continent have increased significantly over the past decade. Most recently, at the 2015 India Africa Summit, India pledged over US$10 billion more in the form of concessional credit and grant assistance.[iii] Indian President Ram Nath Kovind recently announced that his maiden overseas visit will be to Djibouti and Ethipoia, reinforcing the importance the current government attaches to Africa. The question of how India responds to state fragility in Africa thus assumes critical significance. While the index is, without doubt, deeply contentious—it ascribes a static set of standards to ascertain legitimate statehood–it nonetheless highlights the varying levels of instability and fragility in the African continent. India’s engagement in Africa might also provide a window into unpacking the trajectory of its development partnerships globally. After all, it is projected that by 2030, the share of global poor living in fragile and conflict-affected regions will reach 46 percent, up massively from 17 percent today. It is important to understand how India as an emerging economic and military power will help shape global security and development architectures.

This brief examines India’s current response to state fragility in Africa. The first section provides an overview of India’s investments in African development and security and the second examines in detail the cases of South Sudan and Libya, two of the top recipients of Indian investments, and both among the top 20 in the Fragile States Index. New Delhi typically does not use the language of “fragile states” nor does it have a specific policy framework guiding its engagement in such contexts; its position must therefore be inferred from its investments in African development and security. The third section then looks at India’s posturing at global platforms, to see whether there is continuity between New Delhi’s approach to fragility in Africa and its global pronouncements. The brief concludes with an outline of future policy trajectories and recommendations relevant for India.

A few points should be noted at the outset. First, as a recent paper by ORF’s Malancha Chakrabarty shows, academic and policy literature tends to exaggerate the scale of Indian investments in Africa. Over 90 percent of India’s investments are in Mauritius, which is a tax haven; it is then ‘round-tripped’ back to India, making use of the double taxation avoidance agreement between Mauritius and India.[iv] It is thus not surprising that India does not have a formally articulated policy framework for how its responds to state fragility in Africa. India’s investments in Africa are nonetheless significant because they are being packaged as “development partnerships” and are poised to grow in scope and scale as New Delhi positions itself as a leading power.

Second, before comparing the approach followed by India to that of OECD-DAC donors—the so-called traditional donors—an important difference in historical trajectories must be recognised. Development interventions by these traditional donors are at least partly informed by a sense of historical responsibility and moral obligation, rooted in their colonial histories. Accordingly, for much of its history, development assistance has been intertwined with a narrative of “charity”. India does not have a comparable historical experience that gives it either a sense of global obligation or an impetus for a global mission. If anything, its experience as a former colony itself, and its leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) leads it to reject the hierarchical and paternalistic relationship fostered through “charity”; what India emphasises instead are ideas of reciprocity, mutual benefit, and partnership.[v] Traditional donors are also motivated by the perceived threat to national security from persistent underdevelopment and volatility in the periphery. India’s security concerns, on the other hand, are not defined so widely or globally – rather, the most immediate and direct threats emanate in its immediate neighbourhood. It is necessary to recognise these distinct historical trajectories when framing expectations and evaluations about the role of emerging powers like India as providers of global development and security.

Third, it is also important to recognise India’s long-standing commitment to the principles of sovereign equality and non-interference, shaped partly by history – its fight against colonial rule and its leadership of the NAM – and partly by strategic and security concerns – to deter external interference in India’s management of its multiple internal insurgencies. While India has ignored these principles at multiple occasions, choosing to prioritise its own national security interests,[vi] this principled and strategic posturing has also led to India’s rejection of the narratives around ‘fragile states.’ New Delhi has argued that it imposes an external standard of legitimate statehood and provides a basis for military intervention, thereby violating the principle of sovereign equality.

[xxxvii] Rahul Rao argues that it was only when Ambassador Hardeep Puri represented India at the UN, from 2009 onwards, was there a change in India’s official position. This was due to the different ideological make-up of Puri as well as the withdrawal of the leftist parties from the ruling coalition government in India.

[xxxviii] Statement by Ambassador Hardeep Singh. Puri, Permanent Representative of India to the UN at the Informal Interactive Dialogue on the Report of the Secretary General on the Responsibility to Protect: Timely and Decisive Action, 5 September 2012.

देश में एक करोड़ यात्री प्रतिदिन कर रहे हैं मेट्रो की सवारी: पुरी ..

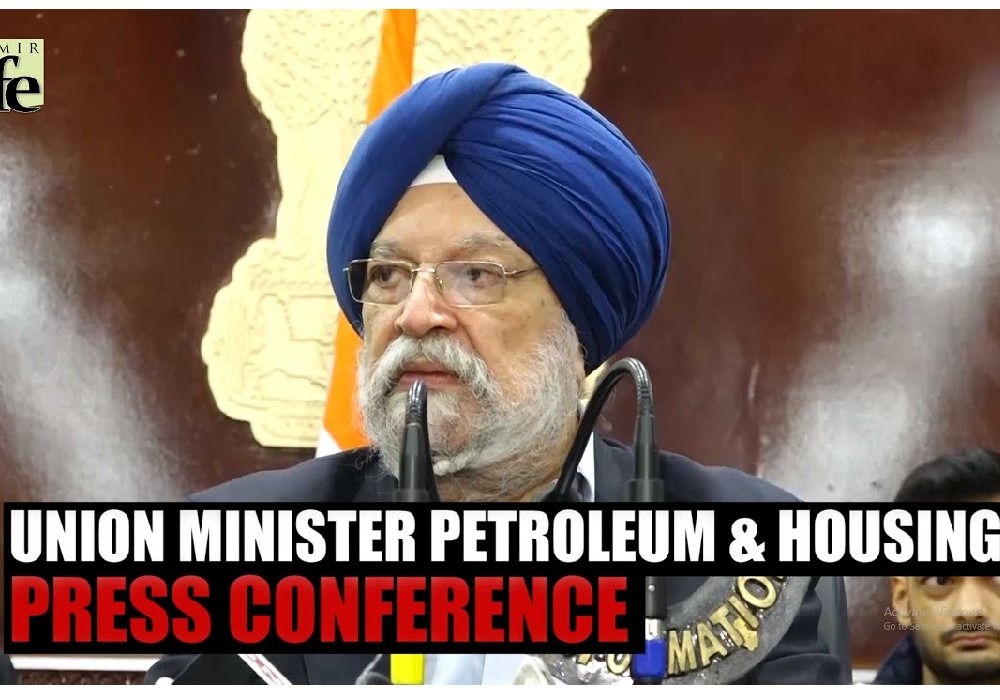

Union Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas and Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri addressing a press conference in ..

Joint Press Conference by Shri Hardeep Singh Puri & Dr Sudhanshu Trivedi at BJP HQ| LIVE | ISM MEDIA ..

(3).jpg)

"I wish a speedy recovery to former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh Ji. God grant him good health," Puri wrote. ..