What happens when the government wants your land?

When a 93-year-old school on College Road, a cluster of shops in Purasaiwakkam and over a hundred homes that offerred new life to repatriates from Burma and Sri Lanka in Assisi Nagar were served eviction notices in July for the construction of Phase 2 of Chennai Metro, the affected came together to launch a fight to save their land from the project.

Chennai Metro wanted the land for its Phase 2 which will cover 108 kms and span three corridors. The priority corridors 3 and 5, for which the land is being sought, are to see construction first and will run between Madhavaram – Shollinganallur and Madhavaram – CMBT. The Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has approved funding of Rs 20,196 crore for the priority corridors. The total length of the two corridors is 52 kms.

Residents stand ground

Assisi Nagar is a residential locality developed in the 1970s for people who came to the city from erstwhile Burma and Sri Lanka, as well as low income families. The idea was conceived by one Father Ignatius, who bought the land and handed it over to the community. The community has grown over the past 40 years, with some original inhabitants moving out, and new residents taking their place. A large number of families from the original settlement still remain, having spent over 40 years in the area.

“When the houses were served notice, it came as a shock. We were informed that around 150 houses stand in the path of the proposed metro rail project and we would have to vacate them. We had to mobilise the people and revive a defunct Assisi Nagar Welfare Association in order to get everyone together,” says Veerayyan, the head of the association.

Once the citizens were mobilised, they staged protests, demanding that the eviction be halted and alternatives explored for the construction of the metro. “Our demand was to have the metro re-routed as there was plenty of government land in the surrounding areas. And yet our homes were being taken away for a project that would not benefit most of us,” says John Francis, one of the residents whose home was among those served a notice.

The residents were given 30 days to raise objections before the district revenue officer on receipt of the notice. The welfare association came together and decided to take the legal route once talks with CMRL collapsed. “We approached many of the local politicians to present our cause, but we did not get any relief. Finally, through the All India Fisherman’s Association, we were able to get an audience with Hardeep Singh Puri, Union Minister for Urban Development, who heard our plea. He assured us that he would provide relief to the residents.”

A truce has been reached between the residents of Assisi Nagar and Chennai Metro Rail Limited after this intervention. Veerayyan claims that they have received assurance that the metro will be diverted and made to pass through the government land surrounding the area, including land that belongs to Aavin. “After months of uncertainty, we are at peace for now. The community can finally sleep without worry,” he says.

A school in the way

The story of Good Shepherd Higher Secondary School, however, has not found such resolution. The school has occupied its current premises since its founding in 1925. As per the plans for Phase 2 of the metro, the school is set to lose the building that houses classes 1-5 as well as a large portion of its playground. This has prompted the administration, parents, students and alumni to rally in support of the institution.

“There are 2000 girl children studying in the school. Our voices are all in unison against this move. This is an established educational institution that has produced eminent and responsible citizens for over 90 years. Our question is, why go after a school? What were the alternatives explored? Can you assure us that no stone was left unturned exploring alternative suitable locations before it was decided that the metro station must come up here, even at the cost of a school?” asks Dr Ameeta Fernando, an alumnus and former president of the parent-teacher association.

The anguished alumni and students have also initiated a petition calling for the school to be protected. Concerned parents raise the issue of the loss of an open playground for the children at a time when most schools are run in cramped buildings, with little room for recreation and sports.

The school sought legal recourse and the Madras High court granted a temporary stay on land acquisition pending a personal hearing. After the hearing, CMRL rejected the school’s case and is set to pursue the matter legally.

“We would like public support as this is not just about one school; no school should be affected thus in future. Our voice is not against development, but the question is whether all other options have been considered and exhausted prior to this,” says Ameeta.

Livelihood loss

The impact of land acquisition for Phase 2 is felt by a wide cross section of people, as evidenced by the struggles of traders from Purasaiwakkam. A M Vikramaraja of the Tamil Nadu Vanigar Sangangalin Peramaippu details the issues faced by the traders.

“The alignment of the metro is such that 1500 shops will be lost. This (Metro project construction) is only being viewed as a commercial project without consideration of how it will impact the livelihood of thousands of families. The textile, jewellery and grocery shops that will be affected by the metro will hit the traders hard.”

The traders have already staged protests and shutdowns and have sent representation to the Government to call for realignment, but to no avail. One of their key demands is that when the shops are torn down, it should not just be the owners of the building who are compensated. The businesses that operate from the buildings must receive compensation too, as they will lose the customer base that they have acquired over decades. It is not easy to go set up shop in some other locality, they point out.

However, the traders do not see the legal route as a viable one in the long term; instead they are looking to gather public support for their demands. They plan to stage a three-day shutdown of all shops in the area after Pongal to raise this demand. “The ground work has already begun in our area and we want to mobilise people’s support for our cause; so far, no authority has taken note of our demands or addressed us,” says Vikramaraja.

Are citizen voices heard?

While large public projects involving claim of land by the state have often been met with protests, the methodology of grievance redressal available to affected persons remains fraught. Conversations with those affected reveal the gaps in participatory planning that could potentially minimise damage.

The social impact assessment report submitted to JICA has revealed that public consultation prior to the project saw very little participation from women in the fifteen locations where the consultation was held. Only 12 women respondents were surveyed in over 170 participants in the impact assessment report.

The mandatory, yet perfunctory, public consultations have come under the scanner as well. “The public consultation is an eyewash as the announcement is made in a small column in the newspaper. Many affected persons don’t even know about it and it receives poor response as a result,” points out Vikramaraja.

An official with the CMRL who did not wish to be named said, “There will be protests against any large public project. We had to go through this to get the first phase up and running. That (Metro Phase I) is now being used by many people on a daily basis. These things happen for the greater good. What we are trying to do here is connect an entire city through the metro. It is a massive undertaking.”

देश में एक करोड़ यात्री प्रतिदिन कर रहे हैं मेट्रो की सवारी: पुरी ..

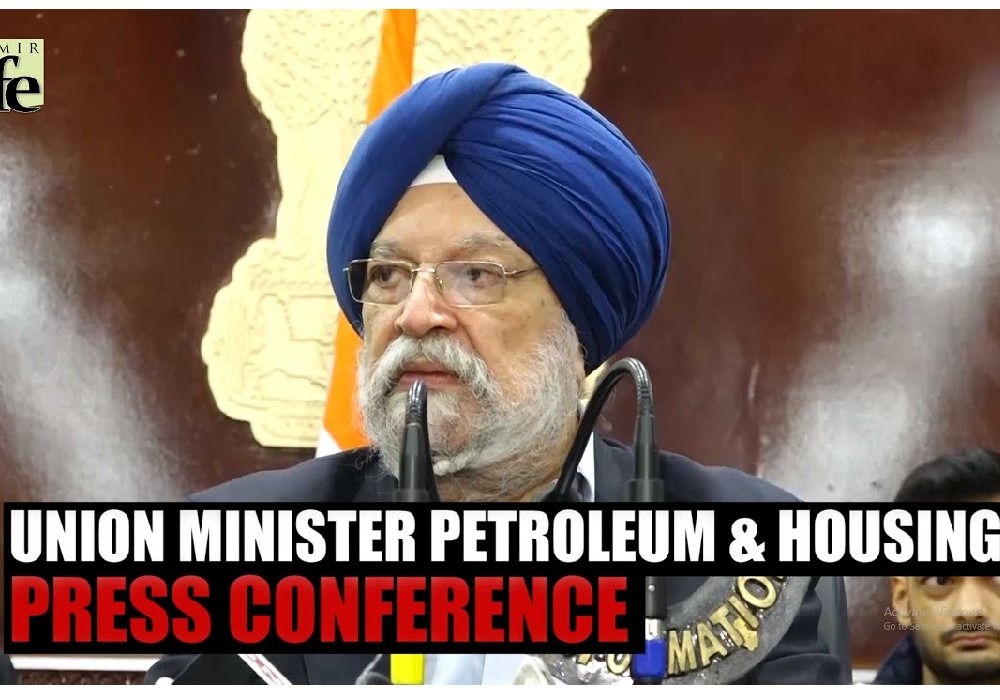

Union Minister for Petroleum and Natural Gas and Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri addressing a press conference in ..

Joint Press Conference by Shri Hardeep Singh Puri & Dr Sudhanshu Trivedi at BJP HQ| LIVE | ISM MEDIA ..

(3).jpg)

"I wish a speedy recovery to former Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh Ji. God grant him good health," Puri wrote. ..